Sección 4.1 Introducción

¶El espacio afín, es un trio de la forma \((V,X,\cdot)\text{,}\) en donde:

\(V\) es el espacio vectorial sobre el cuerpo \(\mathbb{K}\)

\(X\) es el conjunto de puntos

-

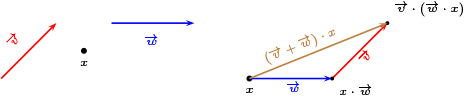

\(\cdot\) es una función dada por:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{cccc}

\cdot : \amp V \times X \amp \rightarrow \amp X \\

\amp (\overrightarrow{v},x) \amp \rightsquigarrow \amp \overrightarrow{v}\cdot x

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

y cumple con:

- \(\left(\forall x \in X \right) \left( \overrightarrow{0}\cdot x = x \right)\)

- \(\left( \forall \overrightarrow{v},\overrightarrow{w} \in V \right) \left( \forall x \in X \right) \left( (\overrightarrow{v}+\overrightarrow{w})\cdot x=\overrightarrow{v}\cdot (\overrightarrow{w}\cdot x)\right)\)

-

\(\left( \forall x,y \in X\right)\left(\exists! \text{ } \overrightarrow{xy}\in V \right) \left( \overrightarrow{xy}\cdot x =y \right)\) donde \(\overrightarrow{xy}\) es el unico vector que envia \(x \) en \(y\text{.}\)

Proposición 4.1.2

Sea \((V,X,\cdot)\) un espacio afín, entonces

- \((\forall x \in X)\left( \forall \overrightarrow{v} \in V \right)\left( \overrightarrow{x \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right)}= \overrightarrow{v} \right)\)

- \((\forall x,y \in X)\left( \forall \overrightarrow{v} \in V\right) \left( \overrightarrow{\left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x\right) \cdot y}=\overrightarrow{xy}- \overrightarrow{v} \right)\)

- \(\left( \forall\overrightarrow{v} \in V \right) \left( \forall x,y \in X \right) \left( \overrightarrow{\left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot y \right)}=\overrightarrow{xy} \right)\)

- \((\forall x \in X)(\forall \overrightarrow{v} \in V )

\left( (\overrightarrow{v}\cdot x= x ) \Rightarrow \overrightarrow{v}=0 \right)\)

- \((\forall x,y \in X)( \forall \overrightarrow{v} \in V )

\left( \overrightarrow{x \left({\overrightarrow{v} \cdot y }\right)}= \overrightarrow{xy}+ \overrightarrow{v} \right)\)

- \(\left( \forall\overrightarrow{v}, \overrightarrow{w} \in V \right) \left( \forall x,y \in X \right)

\left( \overrightarrow{\left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \left( \overrightarrow{w} \cdot y \right)}=-\overrightarrow{v} + \overrightarrow{xy}+\overrightarrow{w} \right)\)

Demostración

-

Sean \(x \in X,\ \overrightarrow{v} \in V \)

\begin{equation*}

\overrightarrow{x \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right)}\cdot x = \overrightarrow{v}\cdot x

\end{equation*}

Por unicidad son iguales

\begin{equation*}

\overrightarrow{x \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right)}=\overrightarrow{v}

\end{equation*}

-

Sean \(x,y \in X,\ \ \overrightarrow{v} \in V\)

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{rcl}

\left( \overrightarrow{xy}-\overrightarrow{v} \right)\left(\overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \amp = \amp \overrightarrow{xy} \cdot \left( -\overrightarrow{v} \cdot \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \right) \\

\amp = \amp \overrightarrow{xy} \cdot \left( \left( - \overrightarrow{v}+\overrightarrow{v}\right) \cdot x \right) \\

\amp = \amp \overrightarrow{xy}\cdot \left( \overrightarrow{0} \cdot x \right) \\

\left( \overrightarrow{xy}-\overrightarrow{v} \right)\left(\overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \amp = \amp \overrightarrow{xy} \cdot x \\

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

Luego \(\left( \overrightarrow{xy}-\overrightarrow{v} \right) \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right)= y\text{,}\) entonces

\begin{equation*}

\overrightarrow{xy}-\overrightarrow{v}=\overrightarrow{\left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right)y}

\end{equation*}

De lo cual se tiene (e)

\begin{equation*}

\overrightarrow{y \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right)}=\overrightarrow{yx}+\overrightarrow{v}

\end{equation*}

-

Sean \(\overrightarrow{v} \in V, \ \ x,y \in X \)

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}[b]{rcl}

\overrightarrow{w} \amp = \amp \overrightarrow{\left( \overrightarrow{v}\cdot x \right)\left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot y \right)} \\

\overrightarrow{w}\cdot \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \amp = \amp \overrightarrow{\left( \overrightarrow{v}\cdot x \right)\left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot y \right)} \cdot \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \\

\overrightarrow{w}\cdot \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \amp = \amp \overrightarrow{v} \cdot y \\

-\overrightarrow{v}\cdot \left(\overrightarrow{w}\cdot \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot x \right) \right) \amp = \amp - \overrightarrow{v} \cdot \left( \overrightarrow{v} \cdot y \right) \\

\left( - \overrightarrow{v}+ \overrightarrow{w}+\overrightarrow{v} \right)\cdot x \amp = \amp \left( -\overrightarrow{v}+\overrightarrow{v} \right) \cdot y \\

\overrightarrow{w} \cdot x \amp = \amp y \\

\overrightarrow{w} \amp = \amp \overrightarrow{xy}

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

-

Sean \(\overrightarrow{v} \in V\text{,}\) \(x\in X\) tales que \(\overrightarrow{v}\cdot x= x \text{,}\) pero \(\overrightarrow{0}\cdot x= x \) luego tenemos que

\begin{equation*}

\overrightarrow{v} = \overrightarrow{xx}= \overrightarrow{0}

\end{equation*}